PREFACE

to

Blues lyric poetry: A Concordance

by

Michael Taft

(

The history of this

concordance is a long one. The present volumes have grown� - perhaps

"evolved" is a better word - out of fifteen years of studying and

thinking about the lyrics of commercial "race record" blues. Over the

years of listening to and reading blues lyrics, I came to realize that the

blues singers employed a type of formulaic structure in the composition of

their songs which was somewhat similar to that of epic singers far removed in

space and time from these Afro-American artists. While I understood this

formulaic system in an intuitive way, I found it difficult to describe in a

concrete, quantitative fashion the extent and nature of the blues for�mulaic

system. My problem was that in order to discover those linguistic forms which

were semantically or syntactically close to each other, I had to re-order or

"decon�struct� lines and phrases in the blues texts. While my auditory

sense sparked my intuitive understanding of the blues, I had to be able to

visualize the songs in a form different from that printed in anthologies or

transcribed from records if I was to find a concrete basis for my intuition.

My first attempt at

deconstruction was manual. I laboriously wrote down phrases from the songs -

one phrase to a separate sheet of paper. After two hundred songs, I amassed a

collection of sheets which filled seven loose-leaf binders. I had succeeded in

deconstructing a small portion of the corpus, but it was apparent that I had

not succeeded in making these re-ordered texts accessible or

"visible" for the kind of analysis in which I was interested.

However, in 1974 I met Michael Preston when he passed through Newfoundland. The

result of our discussions convinced me that the only

way to re-order a massive corpus of texts was to use a computer. This revelation could not have come at a better time,

for I was in danger of suffering the same fate as poor Alexander Cruden, the

eighteenth-century compiler of a concordance to the Bible, who worked on his

magnum opus between bouts in the madhouse (see the life of Cruden in Cruden,

pp. 5-10).

Thus it was that I

began preparing blues texts for concording; a process which involved

keypunching each line of each song onto a card, labelling that card with a code

for the singer and song, and shipping the cards to

The

word "generations" accurately reflects the growth of this project.

The very first blues concordance was an ugly child: printed on large,

cumbersome, green�striped computer sheets, all in capitals, full of symbols

which should have been sup�pressed in the print-out, and of course full of

typographical errors which I never bothered to correct in my keypunching

frenzy. In addition, this first generation was split into three unequal parts,

since the concordance-generating program, at that time, could not handle more

than one thousand texts and my corpus contained over two thousand separate

songs.

As ugly as this

child was, it was usable, and led to the completion of a formulaic analysis of

blues lyrics (Taft, "Lyrics"). But further, more useful generations

followed. The fascinating thing about

working with computers in the humanities is that as one works, the computer

hardware and computer programs become more and more sophisticated. For example,

during the course of this project, the keypunch machine, once so ubiquitous on

college campuses, became a technological dinosaur (I worked with the last one

to be found on the University of Saskatchewan campus) as it was replaced by the

terminal. The

concordance program also evolved from a difficult, jury-rigged affair to a

sophisticated, multifaceted and flexible system for the re�ordering of texts.

Thus, I have had the opportunity to race along on a parallel path with a

technology whose advancement must be timed in months rather than decades.

But at some point

one must cross paths with that technology and decide that the state of the art

has reached a stage which comes up to one's expectations. This

work, then, is the once-ugly child of years past, now matured and ready for

public scrutiny. In other words, the

present state of computer hardware and software allows texts to be re-ordered

so that structures once invisible can be clearly seen and understood even by a

reader who has had no experience with print-outs, terminals or computer

language.

The present work

re-orders over two thousand commercially recorded blues lyrics of the

"race record" era; that is, blues sung by Afro-Americans and produced

in special series by the major recording companies in the

But what are these

problems? The

first questions which the compiler of a folkloristic concordance must ask are

what is the definition of the text and, of all possible folklore texts, which

should be included in the corpus? The literary concor�dance-maker

can more simply demarcate his textual boundaries by stating that �this

concordance will include all works by author X" or "this concordance

will include a sub-set of works (poems, essays, a

single novel) by author X." There might be certain problems with texts of

"questionable authorship" or "attributed authorship" in

literary concordances, but for the most part the corpus is well defined by its

author and literary form.

The folklorist,

however, has a much harder time defining his corpus. His texts will most likely

have been performed by a number of people, perhaps from several generations or

from different cultures and geographical areas (imagine, for example, a

concordance to ghost legends). In addition, folk-literary forms such as ballad,

legend and proverb defy clear definition. Indeed, over the last century, one of

the major preoccupations among folklorists has been the definition and

redefinition of terms, and the battle is far from over. Inevitably, the

folklorist must rely on what Utley called "operational definitions�; that

is, the folklorist must set rather arbitrary criteria for inclusion or

exclusion of a text from his concordance. One hopes, of course, that the

arbitrariness is not random, but carefully considered and based upon a clear

under�standing of the folk-literary tradition from which the texts have been

culled. In short, although the folklorist must make fundamentally etic

decisions in defining his corpus, we must be aware of emic classifications (see

Dundes).

Therefore,

the texts included in this concordance represent a specific under�standing of the

term "blues." From at least 1850, the word has been used to define

many different forms of popular song (Taft,

"Lyrics," pp. 60-61). I have already explained some of the narrowing

criteria which I have chosen for this study: Afro-�American songs, commercially

recorded between the years 1920 and 1942. As well, the songs must be of a certain

form which seems to define "the blues" from the point of view of the

singers themselves. Because I have

already discussed the form and structure of the blues in some detail in the

companion volume to this study (Taft, Blues),

I will only summarize the operational definition here: the blues is a secular

song composed of rhyming couplets in which one or both lines of the couplet may

be repeated one or more times and in which the couplet itself might be embel�lished

with refrains. These refrains may take either the blues-couplet form or any

other form, but it is the blues couplet itself which is the defining feature of

this song form.

If a song fits all

of the above criteria- then it is eligible for inclusion in the concordance. But

the problem of criteria raises another question which plagues the folklorist

more than the literary concordance-maker: how large should the corpus be? The literary scholar has the luxury of a limited

"bookshelf" - the complete works of

an author are finite and knowable. But

this cannot be said of folk literature, for the folklorist's bookshelf is

either infinite or only partially accessible. How many ballads have been sung?

How many jokes have been told? Even if one limits

the folkloristic bookshelf through an operational definition - texts performed

by certain people at a certain time and having a certain form - chances are

that much of this limited book�shelf would still remain inaccessible.

This is certainly

the case with the blues. My operational definition limits the number

of texts which I might choose for the concordance. But despite the fact that I

have eliminated the thousands of non-commercial blues, white blues, post-war

blues, and songs called "blues" which do not conform to the couplet

structure outlined

above, I have still left myself with a huge corpus of texts

- perhaps in the order of ten thousand songs. Although ideally this concordance

should include all pre-war, Afro-�American commercial blues, only about one

fifth of� the

"bookshelf'� was available to me. Because race records are a part of the

ephemera of American popular culture, many have completely vanished, leaving

only a trace in the ledger books of recording companies. Other texts survive on

only a handful of discs which may be too scratchy to reissue or which belong to

collectors who have not been canvassed by reissue record�ing company officials.

Because I have

relied upon long-playing albums of the blues reissue trade (see the

Discography) rather than on the original 78rpm discs for my research, my corpus

is not only limited to those songs available on modern phonodiscs but is

somewhat distorted by the particular biases of these reissue recording

companies. In

short, some blues singers have been reissued many times over while others have

been ignored. Historically,

reissue companies have favored the more "traditional" blues over the

more "sophisticated" big-city and vaudeville blues in their reissue

schedules. Of course, I purposely searched for albums which contained the

less-known (or less popular) blues singers in order to counterbalance this

unwanted overlay on my crite�ria for the corpus, but despite my search, there

are no examples from such prolific artists as Leothus Green, Viola McCoy or

Lucille Hegamin. Other singers, such as Buddy Moss, Mamie Smith or Charlie

Spand, are not represented in proper propor�tion to the number of songs they

recorded. Still

others, such as Tommy Johnson and John Hurt, are probably over-represented (if

that is possible) because of their great popularity in the reissue market.

The only solution

to this unwanted selectional restriction was to include enough songs in the

corpus so that the inclusion or exclusion of any one song or any one artist for

that matter would not be significant. Over two thousand songs sung by about 350

singers representing the wide range of race record blues from vaudeville blues

to downhome blues ensures that this corpus is, if not complete, then at least

representa�tive My decision to limit the corpus to two thousand blues reissued

on albums was also based on certain practical considerations. A reissued song

is, at least ideally, an acces�sible song; the inclusion in the concordance of

some rare, unreissued recording would not help the scholar who wished to check

my printed text against his own copy in his collection of blues albums. The

time involved in tracking down and transcribing unreissued recordings from

record companies and private collectors would have pro�longed a project which

has already stretched beyond a decade. Then too, the addition of one or two

thousand extra songs would have made this concordance even more cumbersome than

it already is. At some point the

very size of a reference work becomes a hindrance to its usefulness.

A

further problem confronts the folkloristic, concordance-maker: In what form

should the oral texts be transcribed and entered into the computer data bank?

Just as the boundaries and definitions of folklore genres are vague, so, too,

are the bound�aries of any given text. What is part of the oral text and what is "peripheral�,

where does an oral text begin and end, and how many performers are actually

presenting the oral text? These folkloristic questions have no set or

agreed-upon answers (see, for example, Georges). Even after one has decided upon the boundaries of the given

texts, one must decide how these oral texts are to be presented on the printed

page and how they are to be electronically stored. The

ethnopoetic struggles of scholars such as Dennis Tedlock, who has tried to

reproduce Zuni texts in a form which captures their expressiveness, is

indicative of the folklorist's problem. By contrast, the literary

concordance-maker has his texts already printed, his boundaries already de�marcated

by the limits of the printed page. The author he is analyzing has chosen the

form of the text for him. I do not mean to suggest that the literary scholar

has no problems in this area (see Bender's discussion), but his problems are

more mechanical and less philosophical than those of the folklorist.

My choices in this

matter have again been based upon my operational definition of the blues and

upon practical matters. As I stated above, the essence of the blues

is the blues couplet. Indeed, the nature

of this type of song is such that one might very well define the genre as one

big blues composed of a large but finite number of couplets, lines and

formulaic phrases; each individual text is but a sub-set of these couplets.

Therefore, this concordance, like its companion anthology, analyzed

"stripped-down" texts (see Taft, Blues)

in which spoken asides, interjections by other performers and parts of the

songs which do not conform to the blues couplet structure have been excluded from

analysis.� Like its companion work, this

concor�dance is more a study of the blues couplet than of the blues song. I

would be the first to admit that these stripped-down versions do not represent

the true nature of the performed text but in order to visualize the

compositional-structural components of the blues couplet - the original intent

of this work - such a redefinition of the bound�aries of the text was

necessary. Indeed, these texts have been stripped down in another way: despite

the number of times a line has been repeated within the couplet, I have

analyzed only one singing of that line. In this way, the concordance reveals

formulaic and linguistic repetitions in the corpus but not the stylistic

repetitions of lines within couplets. From a practical point of view, to have

included every repetition of every line would have burdened the concordance with

duplicate entries and ballooned its size, thereby hiding the more subtle

details of blues lyric structure.

The method of

transcription which I used for this concordance reveals the dif�ference between

literary and folkloristic problems in representing the text. The con�cordance-maker

of printed texts is bound by the orthography and spelling variations used by

the author under analysis; this is especially troublesome for analyses of

medieval and Renaissance works where there might be several spellings for the

same word (see the problem discussed in

Some might argue

that a computer concordance does violence to the text, that its deconstruction

distorts literature and dehumanizes the humanities. But

as computers become more common tools in humanistic research, these worries

will lessen. How�ever, the violence and deconstruction of texts should not be

taken lightly. I have already

stated that the purpose of a concordance is to re-order a text so that the

analyst might visualize it in a new way, but in the case of folklore this

jumbling of the text also reveals the way the singer and his audience see the

text. Once again, the etic and emic properties of this kind of study come to

the fore. Because of the formulaic nature of the blues, there is every

likelihood that when a singer sings a phrase or line, both he and his audience

recognize that particular part of� the song. Perhaps semi�consciously

, they compare this specific singing of the phrase with other singings

of that phrase and phrases similar to it. In an instant, the singer and his

audience compare the way the sung phrase is juxtaposed with others, both in the

song being sung and in other songs which include that phrase. Thus every phrase

in the blues has the potential of literary richness far beyond its specific

usage in one song. Pete Welding has been one of the few to discuss this

property of the blues lyric:

The blues is most

accurately seen as a music of re-composition. That is,

the creative bluesman is the one who imaginatively handles traditional elements

and who, by his realignment of commonplace elements, shocks us with the

familiar. He makes the old newly meaningful to us. His art is more properly

viewed as one of providing the listener with what critic Edmund Wilson

described as "the shock of recognition" a pretty accu�rate

description, I believe, of the process of re-shaping and re-focusing of

traditional forms in which the blues artist engages.

If one were to

illustrate how the audience undergoes this "shock of recognition,"

how the mental processes of the listener bring about this shock, one would

construct something like a concordance. Each word and each phrase would be lined up

against all other words and phrases which are similar to it in all the songs in

which the phrase occurred. By looking down a

page in the concordance one sees in an instant what must occur for the listener

at the moment of "shock." Both the singer and his audience

automatically re-order and deconstruct the text as it is being sung; that

constitutes their method of appreciation and the basis of their understand�ing

of the blues.

That the blues

concordance is fundamentally emic in its format should come as no surprise. I

stated earlier that after listening to and reading thousands of blues lyrics, I

gained an intuitive understanding of the structure and meaning of blues lyrics;

I could sense the formulaic structure even if� I could not explain it. Uncon�sciously,

I was constructing a mental concordance of the lyrics I had heard � adding more

and more texts to that concordance as I listened to more and more blues - so

that I began to sense the same "shock of recognition" that the

traditional blues au�dience must have felt. The computer concordance is simply

a concrete representation of this intuitive process.

I

suspect that literary concordances are similarly emic. After all, Edmund Wilson

was not referring to folk literature

when he wrote of "shock." Current theories of reader-response critics

would seem to indicate that concordances in general reveal something of how we

read. For example, Stanley Fish asks of an utterance, "what does it

do?" (p. 75). One thing it does

is evoke a series of contexts for that utterance and usages of that utterance

which extend beyond the reader's encounter with it in a specific context.

Fish sees literature as existing in the temporal flow of the reader's

experience:

In short, something

other than itself [the written passage], something existing outside its frame

of reference, must be modulating the reader's experience of the sequence. In my

method of analysis, the temporal flow is monitored and structured by everything

the reader brings with him, by his competences; and it is by taking these into

account as they interact with the temporal left to right reception of the

verbal string, that I am able to chart and project the developing

response. (p.

85)

A

concordance would help Fish to chart this response, for it reveals not only the

one-dimensional "left to right" context of a verbal string, but the

three-dimensional place of that string within a body of literature. Of course,

for proper reader-response analysis, one would need a concordance of all the

linguistic experiences of a given reader in order to chart his response. But

even the limited concordances of specific authors and works show the mental

processes at work of author and reader.

It is interesting

that the computer-stored concordance of which this work is only one

manifestation is even more emic than the printed concordance. Just as the blues

listener expands his understanding of the song form with every new blues he

hears, and just as the listener is capable of several different re-orderings

and comparisons at the same time, so, too, the computer concordance has the

same capability. The pres�ent study is only one possible way of

re-ordering a set number of texts. But the data in computer storage can be

expanded by the inclusion of yet more texts, just as a new blues text will be

stored in the memory of the listener. As well, old texts in storage can be

emended to clear up transcription errors. But more importantly, the concordance-�generating

system allows many different kinds of re-orderings. For

example, the words under analysis can be listed according to their sequential

order in the corpus or according to the alphabetical order of the context which

follows the words; they can be presented randomly down the page as they appear

in their line contexts or they can be centered and aligned so that they appear

in a column. The words can be

presented without any context (a simple word index), within the context of

their line, or in a more extended context which makes use of as much space on

the page as possible.

Phrase concordances

analyze repeated strings of three, four or five words. Re�verse concordances

analyze words backwards, producing lists of rhyme-words. Letter concordances

deconstruct the words themselves and re-order the corpus by frequency of

letters. The

corpus itself can be altered so that single singers or specific groups of

singers can be pulled from the data bank for smaller comparative concordances.

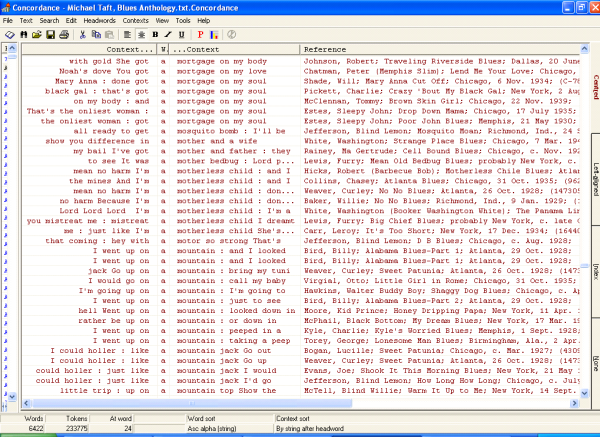

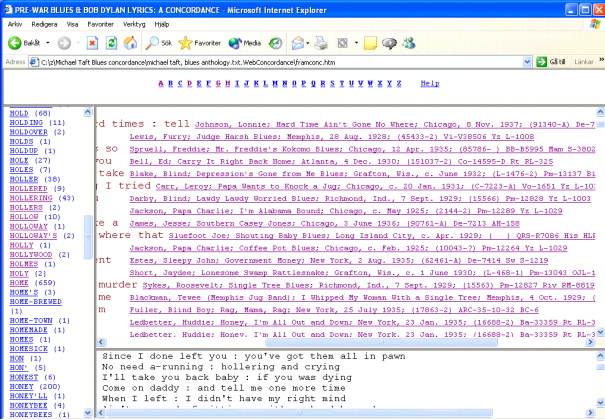

Sample page I of the Concordance on PC

The first sample

page shows one possibility: a phrase concordance which lists all four-word

strings in the corpus. This sample also shows the option of listing the phrases

in the order they appear in the corpus as well as placing these strings in a

center-column alignment. This sample shows the strings within the

context of their poetic lines, rather than in the more extended context of as

much of the song as would fit on a line of the concordance page.

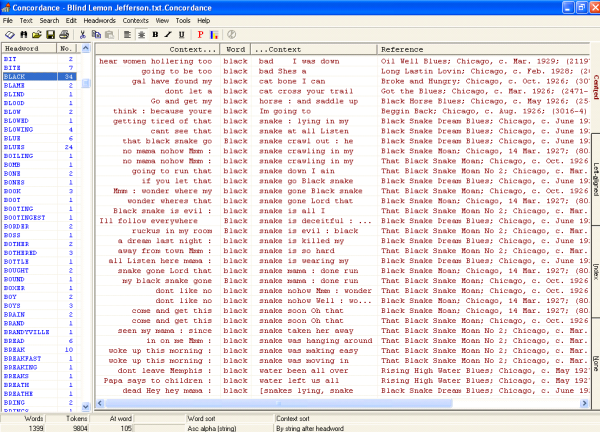

Sample page II� of the Concordance on PC

The second sample

page chooses some of the same options as the first - an unextended,

center-aligned context -�

but it is a selected concordance of the repertoire of only one

singer in the corpus, Blind Lemon Jefferson. In addition, the words under analysis are

listed alphabetically according to the context which follows the words. (Preston and Pfleiderer give further possibilities for

re-ordering texts on pp. 409 -� 423.)

Each type of

concordance allows one to visualize the texts in a new way. The

present work is only one manifestation, only one possibility, among many. In deciding which manifestation to use for this work,

I chose one which most clearly shows the structure of blues lyrics. Rather than

being a form of poetry in which innovative words and phrases are the norm, the

blues relies on formulas, idioms and well-recognized semantic units to convey

its meaning and artistry. An "extended KWIC (key word in context)

concordance" such as the one chosen for this work presents the blues most

clearly as the type of poetry which "schocks" us with repeated and

recoignized phrasing. My choice of this type of format was undoubtedly based

on the same principles as Duggan, who chose a similar KWIC concordance in his

exploration of the formulaic nature of the Chanson

de Roland.

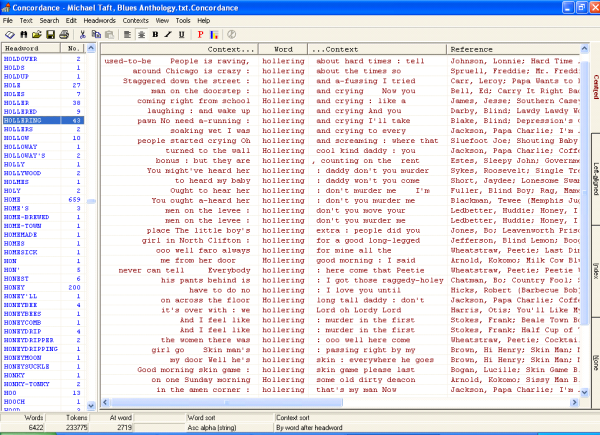

The reader will

notice that the extended KWIC format comprises a list of cap�italized

"head-words" running down the left-hand margin of the page under

which are listed specific contexts for this head-word. The

word under analysis appears in the center of the page, preceded and succeeded

by as much poetic context as will fit on the line of the page. The instances of

the analyzed word are listed in alphabetical order according to the succeeding

context of the song in which it is found. Thus, on the third sample page hollering about is

followed by hollering and; hollering

and crying is followed by hollering

and screaming.

Sample page III� of the Concordance on PC

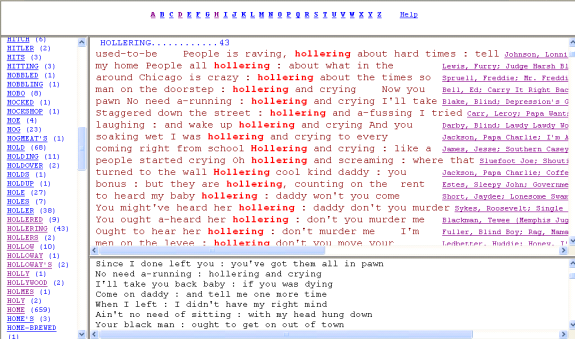

Sample page III� of the Concordance on the� Web

Clicking on the

second instance of� hollering and crying� brings up the

complete transcription of the lyrics, in this case Blind Blake�s Depression�s Gone from Me Blues.�

Sample page III� of the Concordance on the� Web, with the�

Concordance-frame scrolled to the right

Every word under

analysis is identified according to its place in the corpus. Thus, to the right

in the Concordance-frame of the second instance of� hollering and crying appears:

the name of the singer: ����� Blind Blake

the title of the song:���������� Depression Gone from Me Blues

recording place:���������������������������������������

date:����������������������������������� c. June 1932��������������������������������������������

record number:���������������������������������������� (L-1476-2) Pm-13137 Bio BLP-12023

On the bottom frame

the lyrics for this song are shown.

In general, the

word-forms in this concordance correspond to single words as found in a

standard American dictionary. The numbers following the head-words give the

reader the number of occurrences of that word in the corpus; thus, there are

forty-three occurrences of hollering

(or 0,017 % of all occurances), but only two occurrences of hollers. Hyphenated word-forms are

listed under their individual components; for example, a-hollering�, will be found under a in� the

concordance.

For the sake of a

clear, uncluttered page I have included very little punctuation.

The colon (:)

indicates the approximate place of the half-line caesura, which is

characteristic of the blues form (see Taft, Blues,

for a more detailed explanation of the caesura). This mark also helps the

reader's eye to catch the first and second halves of lines. Asterisks (*)

enclose parts of the transcriptions which are questionable: that is, passages

which are only educated guesses at what is actually being sung. These

hypothetical passages may be one word, as in Them Smoky Hollow women:sure

put a *method* on you or phrases, as in *Hollering for a good long-legged man*.

Passages which I have not been able to decipher at all are marked by three

question marks (???) regardless of how long or short these passages might be;

see, for example, hollering (??? you fall).

On occasion, I can only decipher a part of a word, which I then mark with three

question marks and that part of the word which I can decipher; see, for

example, hollering don't you murder me/I'm down in the bottom ???ing for Johnny Rye.

The reader will

notice some words and phrases in brackets ([ ]). These passages occur in one repetition of a

line but not in another. For example, the

phrase, I'm like a [drunk] man �represents the following

repeated line:

Most

times when I get hungry: I'm like a drunk man acting a clown

Most times when I get hungry: I'm like a man acting a

clown

In other instances,

the brackets enclose two or more passages separated by commas, as in hollering: People is [raving, hollering]

about hard times. Here the singer has substituted one word for another in

the repetition of the line:

People

is raving about hard times:tell me what it's about

People is hollering about hard times:tell

me what it's all about

The value of this

new way of visualizing a text is revealed not so much in the use of the

concordance to look up a specific word or phrase, but in browsing through the

work. By browsing, by randomly flipping through the pages and letting one's eye

"be caught" by a particular pattern, one makes discoveries. And these

discoveries are all the more significant because they do not grow out of

preconceived notions about the texts. The concordance forces one to see what

could not be seen before. For this reason, I have not followed the practice of

some concordance-makers who omit certain overly common words (a, the, in, I) from analysis. By

browsing through those parts of the concordance which analyze these less

substantive words, one often finds especially interesting linguistic patterns

and congruencies; for example, prepositions such as in and to reveal patterns

of� phrasing common in the blues.

For each word in

the concordance the percentage of� the total number of� its occurances in the corpus is shown. As one

might expect from lyric poetry, the most common word is I, which occurs 9.887 times in the corpus and makes up a total of

4.229 % of the 233.775 words in the entire corpus.

This may appeal mostly

to the statistician, but it does tell something of the kind of corpus under

analysis. That the blues song is highly repetitive (or formulaic) and that the

blues singer chose to limit the themes of his song to a relatively few and use

only a limited, idiomatic vocabulary in his compositions is evident from these

statistics. The recent concordance to Meredith (Hogan, Sawin and Merrill), by

comparison, reveals a corpus which is less structured and repetitive: 188.440

words compared with the blues corpus�s 233.775, yet 17.967 head-words compared

to only 6.422 for the blues corpus. (These statistics for Meredith will not be

found in the printed concordance but are available from the

electronically-stored Meredith concordance at the Center for Com�puter Research

in the Humanities at the

The information for

each song in the Anthology and Concordance is structured as follows:

Name of singer����������������������������������������

Title ���������������������������������� Long Lonesome

Days Blues

Place and date������������������� ���������������������

Record numbers���������������� (81213-A) OK-8511 Rt RL-315

Name of singer

Where a song is

attributed to a group by Godrich and

Title

The title of the song� as given in

Godrich and

Place

and date

Information on

place and date of recording also comes from Godrich and

Record numbers

The line marked

"record numbers" contains four pieces of information. First the

matrix or master number of the recording is given in parentheses. This number pinpoints

the location and sequence in the daily recording sessions of the record

companies and is important in identifying the relationship of the song to the

entire output of the race record era. In the above example, the master number

is 81213. Within the parentheses following this number is the "take"

number or letter which indicates which version of the song sung in the

recording studio has been transcribed.

Thus, this was the

first (and perhaps only) version of the song recorded by Alexander, since it is

marked "take A." Note, however, that the first and second song by

Luke Jordan are different takes of the same song sung by Luke Jordan and

recorded in succession; they have the same master number but different take

numbers (1 and 2). All master and take numbers are from Godrich and

The next

information on this line is the original catalogue number for the 78rpm

recording of the song. The letters before the dash are an abbreviation for the

record company or label on which the song was recorded (see Abbreviations for

Race Record Labels) and the alphanumerical designation after the dash is the

catalogue number. In the above example, OK-8511 indicates record number 8511 in

Okeh Record Company catalogue. Where a song was recorded on two or more

race record labels, I have indicated only the first label and catalogue number

listed in Godrich and Dixon. In some cases the

recording was never issued, but remained a test pressing or a master in the

possession of the record company. The word "unissued" replaces the

non-existent catalogue number in these cases.

The final

information on this line is the label and catalogue number of the long-playing

album from which the song was transcribed. The label appears as either a two�

or three-letter abbreviation followed by an alphanumerical catalogue designation,

or where the catalogue designation contains no letters, as an abbreviation

attached by a dash to the catalogue number. In the above example, Rt is the label,

Roots, and RL�315 is the catalogue number for the album. For the code to long-playing album abbre�viations, see

the Discography and Abbreviations for Long-Playing Album Labels in the preface

to the Anthology.

***

The Center for

Computer Research in the Humanities and the

References

���������������������

|

Bender, Todd K. |

"Literary

Texts in Electronic Storage: The Editorial Potential", Computers in the Humanities, 10

(1976), 193-99. |

|

Cruden, Alexander. |

A Complete Concordance to the Holy Scriptures of the

Old and New Testament. New York: Dodd, Mead,

n.d. [First ed., 1737] |

|

Duggan, Joseph J. |

A Concordance of the Chanson de Roland. � |

|

� -� �� - |

The Song of Roland: Formulaic Style and Poetic Craft. |

|

Dundes, Alan. |

"From Etic

to Emic Units in the Structural Study of Folktales", Journal of American Folklore, 75

(1962), 95-105. |

|

Fish, Stanley E. |

"Literature

in the Reader: Affective Sylistics." New Literary History (1970). Rpt. Reader-Response Criticism: From Formalism to Post-Structuralism. Ed. Jane P. Tomkins.

Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1980, 70-100. |

|

Georges, Robert A |

"Do

Narrators Really Disgress? A Reconsideration of `Audience Asides' in

Narrating." Western Folklore, 40 (1981), 245-52. |

|

Godrich, John,

and |

Blues & Gospel Records 1902-1942. Rev. Ed. London: Storyville, 1969. |

|

Hogan, Rebecca

S., |

A Concordance to the Poetry of George Meredith. New York: Garland, 1982 |

|

Preston, Dennis R. |

"`Ritin'

Fowklower Daun 'Rong: Folklorists' Failures in Phonology." Journal of American Folklore, 95 (1982), 304-26. |

|

Preston, Michael J., and |

A KWIC Concordance to the Plays of theWakefield

Master. Contextual Concordances. |

|

Taft, Michael. |

Blues Lyric Poetry: An Anthology. New York: Garland, 1983. |

|

� -� �� - |

The Lyrics of Race Record Blues, 1920-1942: A

Semantic Approach to the Structural Analysis of a Formulaic System. Diss.

Memorial Univ. of |

|

Tedlock, Dennis, trans |

Finding the Center: Narrative Poetry of the Zuni

Indians. |

|

Utley, Francis L. |

"Folk

Literature: An Operational Definition." Journal of American Folklore (1961). Rpt. The Study of Folklore.

Ed. Alan Dundes. |

|

Welding, Peter J. |

"Big Joe and

Sonny Boy: The Shock of Recognition." Record notes to Big Joe Williams and Sonny Boy Williamson. Blues Classics BC-21. One

twelve-inch 33 1/3rpm phonodisc. |

|

Wilson, Edmund, ed. |

The Shock of Recognition: The Development of

Literature in the |

���������������������